Can XP Invigorate Microsoft?

Can XP Invigorate Microsoft?

By Hal Plotkin

CNBC.com Silicon Valley Correspondent

Mar 15, 2001 09:00 AM

Microsoft Corp. {MSFT} is billing the pending introduction of its newest personal computer operating system (OS) for consumers and businesses, called Windows XP, as the single most significant upgrade to the firm’s product line since the firm’s groundbreaking release of Windows 95.

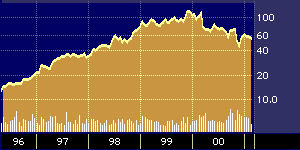

The introduction of that product, which among other things made multitasking a breeze, touched off a multi-year spate of new PC buying along with mushrooming sales of the firm’s compatible software applications. It also contributed to a substantial long-term share price appreciation trend in Microsoft’s stock.

Microsoft 5-year stock performance

But several analysts who’ve taken an early peek at the forthcoming XP say don’t expect that to happen again this time. Although the new XP software will offer some nifty improvements over currently available products, the experts say investors should not expect XP to significantly boost Microsoft’s stock or to revive the sagging PC industry, at least not over the next year or two.

“XP is the first major upgrade since Windows 95,” says Rob Enderle, vice president of the Giga Information Group, based in San Jose. “But it’s not the revolutionary product the business community in particular has been looking for.”

Enderle says he expects initial sales of XP to be modest, especially when compared to the rollout of Windows 95. And that, he says, means consumers and business buyers also probably won’t be flocking to buy new PCs or updated software applications optimized for the new OS either.

“If you don’t buy the new OS, you won’t have any real reason to upgrade the applications,” he says. “And if XP does not do well, it’s going to have a relatively dire impact on Microsoft’s recovery and the rest of the tech sector.”

Minimum system requirements for the new OS, which is slated to be released before the end of this year, are expected to be a Pentium II running at 233 MHz with 64 MB of memory, and at least 1 GB of free disk space.

No prices have as yet been announced, but the company usually charges about $100 for consumer upgrades and roughly $200 for business upgrades of its newest operating systems. In a new and as yet unconfirmed twist, Microsoft is also expected to offer customers the option of buying the new OS on a subscription basis, which would create recurring revenues for the firm.

Analysts generally like the new recurring revenue business model. But they say Microsoft will have to put more goodies under the hood to revive the PC sector’s growth engine.

“The issue for Microsoft is a saturated marketplace for new systems that exposes the firm to the fluctuations in PC sales,” says Chris Le Tocq , an analyst at Gartner, based in San Jose. “The subscription model gives them continuing revenue and one thing Wall Street loves is predictability of revenue. Microsoft would hope to see that predictability reflected in an increased stock price and revenue to both its top and bottom lines.”

But like Enderle and others, La Tocq says there is one not so little problem with that plan.

“Although that’s Microsoft’s goal, if you look at what they’re showing [in pre-release] beta, it would be difficult to call [the new XP OS] a significant improvement,” La Tocq says.

La Tocq says XP appears to be basically a feeder system for Microsoft’s much-talked about Dot Net initiative, which is aimed at capitalizing on the firm’s market-leading OS to build related web-based services. XP users, for example, will probably find an icon on their system that allows them to save photos, not on their hard drive, but rather at an online fee-based web site operated by Microsoft.

The main advantage of the new software, though, is the fact it is based on the more advanced Windows 2000 code, not on the often-buggy consumer-oriented code that underlies previous versions of Windows 95, Windows 98, and Windows ME.

“XP does meet the promise that Windows 98 didn’t in terms of reliability, security and stability,” says Enderle. “But they’re dealing with a very jaded audience.”

An estimated 80 percent of the people who would have otherwise bought a new PC in 2000, for example, said they decided not to because of the trouble they had with their last PC upgrade, according to a recent Giga survey. The troubles cited most frequently included difficulties moving files, applications and address books.

“It was just too painful for them,” says Enderle.

On the business side, the industry analysts say Microsoft will have to offer an OS product that makes managing networks of interconnected PCs decidedly less complex and cumbersome before most business users will make another switch. The company is moving toward that goal, they say, but it will probably be the operating system after XP, or a major revision to XP, before that is accomplished.

“We just don’t see near-term earnings growth for the company,” says David Readerman, an analyst at Thomas Weisel Partners, based in San Francisco, who currently rates the stock “market perform.” Readerman says XP won’t have any material effect on Microsoft’s stock until at least the December quarter, if then.

Even so, there are indications of renewed interest in Microsoft’s stock from major institutional buyers, at least through the end of 2000, the last period for which reliable numbers are available.

Mutual funds were net buyers of Microsoft’s stock in the December quarter, adding 56.9 million net shares to their portfolios over the prior quarter, according to data provided by Thomson Financial. The biggest buyers were the Fidelity fund family, Capital Research and Management, Jennison Associates, and Banc of America Capital Management.

Analysts attribute that buying, in part, to lessening concerns that Microsoft will be broken up as a result of the still-pending federal anti-trust case against the company.

At the same time, however, several other funds have dramatically shaved their exposure to Microsoft’s stock. The Janus family of funds, for example, owned just 5.8 million Microsoft shares at the end of the last quarter, down from 53 million a year earlier.

“Generally speaking, what you’re seeing is selling by the aggressive growth funds and buying by the value guys,” says Peter Jungh, director of Thomson Financial, based in New York.

The irony in that, of course, is that as individual investors bail out of poorly performing aggressive growth funds in favor of value funds they can often end up right where they started – as Microsoft shareholders.